The Nature of Universal Injunctions

The Nature of Universal InjunctionsDuring the initial battles in the lower courts, some critics wondered how a judge in Hawaii could halt an executive order issued by the President. Justice Thomas wondered the same in his concurrence.

To recap, the Supreme Court upheld Trump’s travel ban in a 5-to-4 vote. The majority reaffirmed the President’s power in foreign policy and immigration was not undermined by the often racist and offense remarks made by Mr. Trump. Justices Kennedy, Thomas, Alito Jr. and Goursuch joined Chief Justice Roberts in the majority. Justices Kagan, Sotomayor, Ginsberg, and Breyer dissented.

Although the Court broke into two sides, many of the other justices wrote opinions of their own. Sotomayor and Ginsberg issued a dissent that focused on the discriminatory harm that Muslims would suffer from this ban and the hypocrisy of the majority in a prior case that was ruled on only a week ago.

Justices Kagan and Breyer also dissented, but they were more concerned that the exemption and waiver system built into the nation’s immigration laws was not being enforced by this Administration.

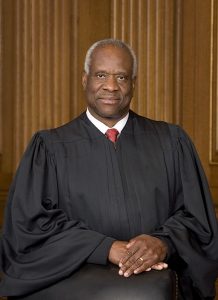

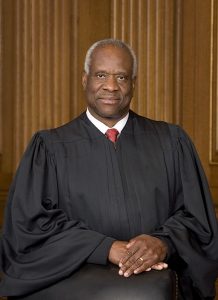

The stranger concurrences came from Justice Kennedy, who is retiring at the end of the Court’s current term, and Justice Thomas. Kennedy joined Chief Justice Robert’s ruling in full, but wrote a page about the importance of the Oath that government employees take prior to entering office. It was Justice Thomas’s concurrence though, that may have the biggest impact on federal courts in the future.

The Nature of Universal Injunctions

The Nature of Universal InjunctionsTo begin with, an injunction is a court order that prevents a party from acting in a certain manner. Universal injunctions apply to the whole of the United States not because the court issuing the injunction has jurisdiction over the entire nation, but because the party before it (the federal government) operates throughout the entire nation.

A federal judge in Hawaii can stop an executive order from the President because the federal government operates in every corner of the nation. The federal government is the same organization everywhere, regardless of whether the case is in Hawaii, Texas, or Maine.

However, universal injunctions are a fairly recent invention that may reshape the relationships between the three branches of government. Although legal conservatives like Justice Thomas have a fair point in questioning their role in America’s legal system, political conservatives like Ben Weingarten of The Federalist should rethink the long term ramifications of universal injunctions before cheerleading their demise.

Certain conservatives like Justice Thomas are not a fan of universal injunctions. Universal injunctions are not a power explicitly given to the judiciary by the Constitution. Instead, they are derived from a Constitution provision that federal courts are to be courts of “law and equity.”

In Great Britain, there were two different kinds of courts. Courts of law could only apply the law and give money damages to prevailing parties. Courts of equity ruled on what was fair and justice for all parties involved and could order that parties act or not act.

The founding fathers thought this division was silly and combined the two systems together. Thus, American courts have the power to issue injunctions, restraining orders, and other legal solutions other than money awards.

Since the Constitution explicitly makes federal courts equity courts, federal courts have constitutional power to issue injunctions. Justice Thomas is slightly misleading when he implies that federal courts have no authorization whatsoever to issue universal injunctions under the Constitution. The issue is not whether a district court judge can issue an injunction against the federal government, but how far that injunction can apply.

There are pros and cons to extending the injunction power against the entire federal government. Justice Thomas lays out the disadvantages in very clear terms: “These injunctions are beginning to take a toll on the federal court system–preventing legal questions from percolating through the federal courts, encouraging forum shopping, and making every case a national emergency for the courts and for the Executive Branch.”

In other words, universal injunctions encourage parties to file in the court that they think will most likely lead to a victory, a practice that judges frown upon as it often politicizes the courts. Having one trial judge issue a universal injunction prevents other trial judges from making a decision, as most trial judges will respect an order made by another judge unless it is overturned by an appeals court.

Universal injunctions are also a burden on the Supreme Court, as they are compelled to hear the case. The justices on the SCOTUS prefer to pick and choose the cases they hear. Most importantly, universal injunctions give federal district courts the power to direct federal policy if they disagree with it. The proper role of the judiciary is to hear cases, not make law.

However, there are also very good reasons for universal injunctions to exist. Universal injunctions are a practical application of stare decisis, the legal doctrine that preceding cases should govern similar cases.

If a trial judge finds that an injunction is necessary, and it is likely that other judges would rule the same, there is no need for other judges to hear the same case after the injunction has been issued. It would be waste of time and judicial resources to rehear the same case in a different circuit or state.

As stated above, universal injunctions are merely extensions of the injunction powers that the Constitution gives federal courts. The federal government and federal law are the same regardless of the state or circuit the parties are in. If a trial court enjoins the federal government from carrying out a certain act or law, logically that order should apply no matter where the government is.

Finally, universal injunctions are an important check on the imperial presidency as it exists today. Congress has either delegated or remained silent on executive abuses of power. Universal injunctions are one way for courts safeguard the people’s rights if Congress refuses to act or conspires with the Presidency to unjustly strip them of their rights.

Political conservatives like Ben Weingarten might see universal injunctions as part of a soft judicial coup by the lower courts against an elected Republican President, but universal injunctions are legal doctrines, not political toys wielded exclusively by one party.

Universal injunctions were issued by trial judges in Texas to stop the Obama Administration’s DACA program. Conservatives could easily find themselves in the same position they were in 2009 and that liberals find themselves in 2018.

Torching universal injunctions just because they were used to temporarily halt a travel ban would be as foolish and shortsighted as it would be if Republicans in the Senate removed the filibuster.

Universal injunctions are a natural extension of the equity power that the Constitution gives federal courts. In fact, universal injunctions have more foundation than the power of judicial review that Chief Justice Marshall read into the Constitution.

Congress should do more to reign in the office of the President (and the current President), but the Courts also have a legal obligation to protect the rights of the people. Universal injunctions could play an important role in upholding that obligation.